"Still bound by Finance Imperialism"

(Or how the Philippines still bound by Yankee-Multinational

Finance capital and the need to put an end to its dependency)

(Or how the Philippines still bound by Yankee-Multinational

Finance capital and the need to put an end to its dependency)

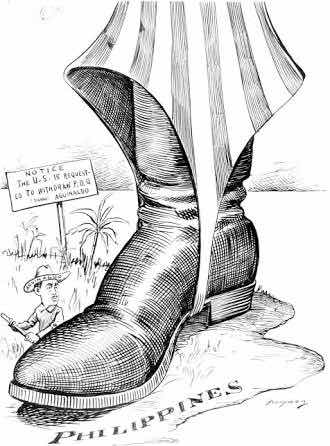

It's been decades passed since Filipinos remember how it's former coloniser self-proclaiming itself as the developer of the islands.

Driven by statements such as "benevolent assimilation", followed by all the numerous contributions shown be it in a form of infrastructure to those of modern machinery, the United States did afford to "brag" that their brand of civilisation created a modern colony enough comparable with the centuries-old ones in the far east, what more that it afforded to provide some semblance of self-rule, which was a product of serious lobbying and negotiations by known Filipinos, that even at the expense of their lives it resulted to various agreements, including those of its fundamental laws that made Filipinos unconditionally indebted to them.

And from those experiences no wonder why the late Franklin Delano Roosevelt stated in his radio broadcast to the Filipinos his promise, that:

“I give to the people of the Philippines my solemn pledge that their freedom will be redeemed and their independence established and protected. The entire resources, in men and in material, of the United States stand behind that pledge. It is not for me or for the people of this country to tell you where your duty lies. We are engaged in a great and common cause. I count on every Philippine man, woman, and child to do his duty. We will do ours.”

Sounds full of optimism indeed those promising times; especially if complimented by some promises from again, according to Roosevelt:

“Over a third of a century ago, the United States, as a result of a war which had its origin in the Caribbean Sea, acquired sovereignty over the Philippine Islands, which lie many thousands of miles from our shores across the widest of oceans. Our Nation covets no territory; it desires to hold no people against their will over whom it has gained sovereignty through war.

“In keeping with the principles of justice and in keeping with our traditions and aims, our Government for many years has been committed by law to ultimate independence for the people of the Philippine Islands whenever they should establish a suitable Government capable of maintaining that independence among the Nations of the world. We believe that the time for such independence is at hand.

“A law passed by the seventy-second Congress over a year ago was the initial step, providing the methods, conditions and circumstances under which our promise was to be fulfilled. That Act provided that the United States would retain the option of keeping certain military and naval bases in the Islands after actual independence had been accomplished.

“As to the military bases, I recommend that this provision be eliminated from the law and that these bases be relinquished simultaneously with the accomplishment of final Philippine independence.

“As to the naval bases, I recommend that the law be so amended as to provide for the ultimate settlement of this matter on terms satisfactory to our own Government and that of the Philippine Islands.

“I do not believe that other provisions of the original law need be changed at this time. Where imperfections or inequalities exist, I am confident that they can be corrected after proper hearing and in fairness to both peoples.”

However, despite that atmosphere of freedom independence doesn't mean an unconditional one people idealised of. For behind that recognition lies agreements wherein it favours its former coloniser especially those on trade, commerce, and security. Roosevelt's death negated his statements, reducing the spirit of independence into a mere testament when in fact retains its vassalage to its master.

There were attempts to insist independence in its fullest form, but it end failed to succeed what more of its leaders maligned, sidelined,or even killed such as in the case of Recto, whose patriotism been cut short by a vial of poison.

And one American legacy was and is how free-trade ideologues have succeeded in imposing their will upon the world under the guise of “globalization.”, those years of reconstruction and genuine self-rule left a generation wherein it was and is easier to think (and therefore to say) that foreign capitalists can act only as catalystic agents to stimulate local investment, what more of its agreements regardless of its unequal character.

Sounds too much as this person ought to say that despite being situated in the Southeast Asian region, that the Filipinos, reared in its colonised upbringings, made itself a stranger among the Asiatic peoples, who although recognises the country's potential as a growing country, it will remain skeptic in its drivel to take its own path-given its inherent dependency to its former coloniser as well as other "developed countries" the country depended on.

Cannot blame them for thinking that way, knowing that as they removed their clutches they started to develop their own using their inherent thoughts as well as those their colonisers taught them; but the Filipino, particlularly its system, treats its own struggle for national rebirth as a cultural facade, and if taken seriously it rather lead to a series of debates. It did tried to stimulate production for its own benefit, especially when patriotic fervour is strong, but it end shelved in in favour of its usual dependence if not getting threatened by those whose policies obviously hinder development if not sneered by promises of cheap goods and hot flow of investments.

Looking back at the past

(and how that past still continues to be debated)

Speaking of debates if not messages from various personages, this writeup looks back at history, especially on how men like Manuel Roxas stubbornly defend the idea of parity rights as necessary for the country's development even at the expense of patrimony.

Based from an old government-sponsored pamphlet containing the speeches regarding the pros and cons of parity rights, the then president-elect explained the United States as a benevolent country that "guides" and "cares" to its underdeveloped counterparts if not trying to relive the past how that country liberated the Philippines from the Japanese occupiers, as well as insisting the benefits of free trade and making the country one of its markets.

Sounds too much as this person ought to say that despite being situated in the Southeast Asian region, that the Filipinos, reared in its colonised upbringings, made itself a stranger among the Asiatic peoples, who although recognises the country's potential as a growing country, it will remain skeptic in its drivel to take its own path-given its inherent dependency to its former coloniser as well as other "developed countries" the country depended on.

Cannot blame them for thinking that way, knowing that as they removed their clutches they started to develop their own using their inherent thoughts as well as those their colonisers taught them; but the Filipino, particlularly its system, treats its own struggle for national rebirth as a cultural facade, and if taken seriously it rather lead to a series of debates. It did tried to stimulate production for its own benefit, especially when patriotic fervour is strong, but it end shelved in in favour of its usual dependence if not getting threatened by those whose policies obviously hinder development if not sneered by promises of cheap goods and hot flow of investments.

Looking back at the past

(and how that past still continues to be debated)

Speaking of debates if not messages from various personages, this writeup looks back at history, especially on how men like Manuel Roxas stubbornly defend the idea of parity rights as necessary for the country's development even at the expense of patrimony.

Based from an old government-sponsored pamphlet containing the speeches regarding the pros and cons of parity rights, the then president-elect explained the United States as a benevolent country that "guides" and "cares" to its underdeveloped counterparts if not trying to relive the past how that country liberated the Philippines from the Japanese occupiers, as well as insisting the benefits of free trade and making the country one of its markets.

They say parity is an extraordinary concession. Why should we give this right, this privilege to Americans when we are not giving them to Englishmen? To us, that is an extraordinary concession. But so are the concessions which Americans are giving to us. Not only extraordinary but very extraordinary, not only very extraordinary but unprecedented in the whole history of the world since the dawn of civilization. They say that "parity" is a concession demanded by Wall Street in the United States in order to exploit this nation. Where is the authority for that statement? Wall Street is not interested in the Philippines. America is not an Imperialistic nation. Not because Americans are angels, but because America is such and wealthy nation and has such tremendous resources that she does not have to be an imperialistic nation. An Imperialistic nation arises when that nation needs products or goods vital to her existence. So if that nation cannot get them in good fashion, it grabs the territory that has them.

America has an excess of raw materials. America does not need raw materials from the Philippines. It might be convenient for the Unitef States to have some raw materials from the Philippines like Copra, like Hemp, like Tobacco, or Shell Buttons. I wonder how many nations would be imperialistic just to get shell buttons! I wonder how many nations would become imperialistic to het copra from the Philippines when copra is produced in many parts of the world; when everybody knows that there are many well-known substitutes for vegetable oil. Hemp? Everybody knows that during the war we did not export a single poind of hemp from this country. And yet America did not die. There are many other fibers that can substitute for hemp, and steel cables and synthetic materials can be fashioned now for use in place of cordage made from hemp. There is nothing we can produce in this country that is absolutely necessary to the economy of the United States.

But they say that the concession we grant to the United States is extraordinary. So is the free trade granted to us by America extraordinary. What nation in the world would not want to enjoy free trade with the United States? Is there any nation in the world that would not give quite a lot for the privilege of selling in the great Ametican market? But contrary to her traditional foreign policy, contrary to her commitments in many powers, America has entered into an agreement with the Philippines whereby for 28 years, Philippine products will be admitted into the United States, free of duty, with certain modification at the end of the first eight years. Isn't that extraordinary?

- Manuel Roxas

From this, one would say that his statement was more of a reaction from a nationalist-oriented policy brought about by the Commonwealth and the Japanese Occupation. Roxas sought that with the United States as an important ally in Asia, it also means better prospects of assistance in various forms of development, even at the expense of local expertise- especially those of sugar interests, which saw in those agreements as their economic salvation.

And knowing that as the country was severely tarnished by the war, and its economy struggling due to low output growth and with high unemployment rates, Roxas finds it necessary those US-sponsored acts (Bell trade Act and War Damage Act) in order to support reconstruction activities regardless of being seen as a stumbling block to the full flowering of Filipino nationalism particularly those of economic protectionism and domestic-based economic development- if not a means to retain the friendship of American officials who had helped whitewash him of charges of wartime collaboration with the Japanese occupiers.

Ironically, Roxas himself was once advocating Filipino products and ingenuity through his "Bagong Katipunan", so for sure one would think why would he end becoming an American stooge? Sounds opportunistic isn't he? And in speaking of "stumbling blocks", issues like sovereignty, the right to tariff protection, currency autonomy, and taxing authority, hath been the topics which both those in favour and those who oppose been debating about.

On the other hand, a statement from the late Claro M. Recto recalled a prewar attempt to industrialise the country only to be blocked by the policies brought about by its trade relations with its colonial master. From this, the late senator expressed seriously that the country, being independent has to create its own direction than retaining its vassalage that continues until present.

And knowing that as the country was severely tarnished by the war, and its economy struggling due to low output growth and with high unemployment rates, Roxas finds it necessary those US-sponsored acts (Bell trade Act and War Damage Act) in order to support reconstruction activities regardless of being seen as a stumbling block to the full flowering of Filipino nationalism particularly those of economic protectionism and domestic-based economic development- if not a means to retain the friendship of American officials who had helped whitewash him of charges of wartime collaboration with the Japanese occupiers.

Ironically, Roxas himself was once advocating Filipino products and ingenuity through his "Bagong Katipunan", so for sure one would think why would he end becoming an American stooge? Sounds opportunistic isn't he? And in speaking of "stumbling blocks", issues like sovereignty, the right to tariff protection, currency autonomy, and taxing authority, hath been the topics which both those in favour and those who oppose been debating about.

On the other hand, a statement from the late Claro M. Recto recalled a prewar attempt to industrialise the country only to be blocked by the policies brought about by its trade relations with its colonial master. From this, the late senator expressed seriously that the country, being independent has to create its own direction than retaining its vassalage that continues until present.

There was an attempt in the Philippines at industrialisation. An attempt embodied in a programme enunciated by his excellency in 1933 when he made his then very famous, although now forgotten speech, before the student body of the Ateneo de Manila. This attempt, this programme of industrialisation was formally announced by the late President Quezon in his first inaugural address as president if the Philippine Commonwealth.

President Quezon had six years before the war to industrialise the country. We know that almost nothing was accomplished. And not for lack of money. In those years millions were pouring into the Philippines from the excise taxes that were being collected from our products in the United States. If President Quezon was not able to achieve the industrialisation of our country- ably assisted through was for some years by our present president who was then the Secretary of Finance- let us not ascribe this failure either to the President or to his Secretary of Finance.

In all justice, the blame lies in, the main cause is, our free trade relations with the United States.

And the poof of prewar attempts for industrialisation was characterized by an effort to free the Philippines from foreign domination, during which was born the Philippine National Bank that broke the country away from the dominance of such foreign banks as Bank of America, National City Bank and Hong Kong Shanghai Bank. Every effort was made to be economically self sufficient with the birth of the National Development Company and its subsidiaries like the National Coconut Corp. (NACOCO), National Food Corp., National Textile Corp., Rice and Corn Administration (RICOA), among others, liberating the country from the monopoly of multinationals like Proctor and Gamble, Unilever, and importers of food and clothing.

Even postwar industrial institutions like the private-owned Republic Flour Mills and the Philippine National Oil Company, were also products of those attempts, whose personages behind were driven by the ideal of breaking away from multinational dependency and to assert independence via a self-reliant economy.

Other than Recto, Rafael Alunan Sr. also recognises the need to revive Philippine industry through reconstruction and investing on Filipino ingenuity as necessary ensuring national survival in the time of war, with himself as secretary for Agriculture and Commerce:

- Claro M. Recto

And the poof of prewar attempts for industrialisation was characterized by an effort to free the Philippines from foreign domination, during which was born the Philippine National Bank that broke the country away from the dominance of such foreign banks as Bank of America, National City Bank and Hong Kong Shanghai Bank. Every effort was made to be economically self sufficient with the birth of the National Development Company and its subsidiaries like the National Coconut Corp. (NACOCO), National Food Corp., National Textile Corp., Rice and Corn Administration (RICOA), among others, liberating the country from the monopoly of multinationals like Proctor and Gamble, Unilever, and importers of food and clothing.

Even postwar industrial institutions like the private-owned Republic Flour Mills and the Philippine National Oil Company, were also products of those attempts, whose personages behind were driven by the ideal of breaking away from multinational dependency and to assert independence via a self-reliant economy.

Other than Recto, Rafael Alunan Sr. also recognises the need to revive Philippine industry through reconstruction and investing on Filipino ingenuity as necessary ensuring national survival in the time of war, with himself as secretary for Agriculture and Commerce:

"More and more, the production of essential commodities is being increased to replace finished products that had to be imported formerly. Among the goods now being turned out by factories to replace the old imports are cassava flour, corn flour, rice flour, in substitution for wheat flour; alcohol for motive power to replace gasoline; cleanser, toilet soap, canned goods, etc. The production of toilet soap has been expanded to an appreciable extent, and filter mats made of coir are being manufactured to be used by soap and lard factories in lieu of asbestos.

Some 1,500 local factories operating in Manila and in nearby provinces are now engaged on the processing and manufacturing of goods for everyday use, such as flour, starch, soap, matches, preserved fish, chocolate, coffee, biscuits, and other foodstuffs, etc. This is an encouraging indication of the significant changes in the phases of Philippine industries."

- Rafael Alunan Sr.

And as a patriot perhaps both Recto and Alunan Sr. expressed concern and hope that a country, if truly adheres to its desire for progress and retaining its independence has to painstakingly set the foundations such as those of a self-reliant economy. The former knows that the country did have funds to industrialise if not for the policies that hinders it, while the latter, knowing that the country being occupied by a wartime power, tried to make sure that the country least stimulate enough to ensure its survival.

But again, the postwar generation and its succeeding ones left an impression that foreign investment if not being lended by multinational moneylending agencies as necessary for national development- leaving the country at the hands of commercial interests instead of building solid foundations such as those of industry. True that the agreements lasted for several decades (until 1974), but the impression continues as there are those who actively seeks foreign investment using a variety of alibis such as to generate employment, and laws such as the Foreign Investment Act (R.A. 7042, 1991, amended by R.A. 8179, 1996) gradually liberalized the entry of foreign investment into the Philippines.

Still, the debate continues

(With same entites benefiting)

As in the past, the debate between economic protectionism and liberalisation remains especially amongst the learned. Both did spew words like "oligarchs" if not "sellouts", given their interests prevailing than those of the people- but they fail to distinguish which is protectionist or liberalist among the elites whose primary intent is to maintain their interests.

They look at Ayala, Sy, Ty, Tan, Pangilinan as examples of those elites. Of course they appear to be privileged, Noblesse Oblige-driven personages in the socio-economic arena, trying to make profit while throwing some crumbs in its tiresome subjects. They would done themselves in Barong Tagalog and singing the national anthem, putting some patriotic flavor in their statements and promising to support various forms of economic developments which includes currying foreign investment and keeping wages low for the workers; but, after hearing statements from the government promising to curb their power in favour of empowering the commons, have they already curbed? For sure apologists would have cited the examples of Lucio Tan and Mighty Corporation, if not threatening the Lopezes and Pangilinan, but how about the other bigger ones like those who ruled over the enclaves of Makati and Pasig?

So are the multinationals whom been described as an "alternative" to those oligarchs. With "economic liberalisation" presented as an alternative, the lessening of government restrictions, privatisation, and subservience to the international market has been the agenda that pleases those of the compradores and bureaucrats. They would even make various alibis such as maintaining or increasing their competitiveness as business environments, if not bluntly stating that only through globalised capitalism, with its so-called free markets and free trade, or even free borders and less to none government interventions, a literal interpetation of laissez faire, as the best ways to build wealth, distribute services and to grow a society's economy.

but come to think of it- if protectionism meant economic power at the hands of the oligarchs, then how come economic liberalisation also involves the same oligarchic entities who stubbornly keeping their interests? Isn't that Liberalisation meant dismantling their power? Yet how come the compradore-landlord nature of these oligarchs find economic liberalisation pleasing as it "updates" their antiquated existence? The ruling class hath remain united for an oligarchy to remain in power and maintain its survival. They see appeals as thoughts to toy with- the way they did made factories out of patriotic sentiment, while at the same time privatising state assets to curry outside investment. The ruling class doesn't really care about the commons despite throwing scraps and crumbs at them-for least it provides them with sustenance so to speak in exchange for unjust agreements and conditions.

In fact, some of them would even look at the example of Japan during the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate and the rise of the Mikado as the absolute ruler- it did curry foreign investment, technology, knowledge, anything necessary for its modernisation; but, the government was also involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period, as well as built railroads, improved roads, and inaugurated a land reform programme to prepare the country for further development. so was the Zaibutsus who were once former Daimyos and Samurais who end invested in the use of modern technology both for the country and their interests, others, like in the case of Matsushita, did afford to babble "social justice" as one of its policies behind their industry, as if trying to put morality in managing the entire enterprise.

So was Taiwan or even South Korea that did the same patriotic-driven procedure: It carried out an import substitution policy, taking what was obtained by agriculture to give support to the industrial sector, trading agricultural product exports for foreign currency to import industrial machinery, thus developing the industrial sector. It did raised tariffs, controlled foreign exchange, and restricted imports in order to protect domestic industry. But these came the birth of conglomerates amongst the privileged.

These experiences may sound quite decades if not centuries old, but in developing countries it continues to remain relevant given their resource, labor power, and patriotic desire for full-scale development. In fact, these countries also happened to have their own elites, but in fairness to them it tried much to prioritise national interest, the problem in the Philippines was and is- how these developments which meant for the development of the country been treated half-hearted, if not wholly rhetorical- or bluntly telling that not all of them was carrying the same mindset as Salvador Araneta or Claro M. Recto.

The Oligarchs, regardless of their adaptability to modernity, would rather act Lockean as they tried to retain a good, old-fashioned system of feudalism and slavery in order “that we may avoid erecting a numerous democracy…” It is natural for them to see an unjust order, if not distorting the idea of "noblesse oblige" for their benefit especially in a time of neoliberal-globalist "modernity". On the first place, if the Philippines experience progress, then why agriculture remains less developed than those of its neighbours? Of less inclination if not total disdain towards industrialisation and promotion of science and technology? And rather a massive consumerist base depending on consumer goods? The compradore nature of these oligarchs rather clings to their space despite recognising the need for industrialising a country abundant in resources-but will they do so? They would rather act Lockean if not almost Jeffersonian as they insist the agrarian-commercial nature of the country and hath to be retained while letting some manufacturing be set upon for a trade. In fact, speaking of that former US President, Erik Maria Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn described him "as an Agrarian Romantic who dreamt of a republic governed by an elite of character and intellect".

Perhaps in a desire to have an enlightened elite, very few of these "elites" could ever grasp the enlightenment as what Salvador Araneta or Claro M. Recto has especially if the desire is for the development of the nation and the welfare of its people, or even those of Luis Jalandoni and Jose Maria Sison who transcend their class upbringings as he favours those of the commons a la Frederick Engels whose experiences as a manager made he transcend from his background and instead favours the need for revolutionary change. All imbued with a good character and intellect, these had to go down from the hill as they heed and learn from the common folks which actually constitutes a nation.

Conclusion

Sorry if to look at the past for an example, but that past remains relevant amongst those who wanted to see the country remain contented in its setting as well as those who insist to break away from it. True that the Philippines is a wealthy country. Wealthy country whose majority of its inhabitants wallow in poverty- and everyone still always say with pride that the land is rich in natural resources from the mountain to the sea, but who is to benefit that wealth what more of the development being shown and felt upon? The late Roxas, and so is his successors, would rather say that let the foreigners do the job while his compatriots to the manual task-or as what he said:

"Some Americans are coming―trained engineers, trained technicians and technologists, trained miners, trained lumbermen, who will help us finance and develop our natural resources."

True but the question is, who is to benefit that? The people who invest their brawn or those who profit from it? In fairness, there are good foreigners who seriously and selflessly focus on developing the country, but most rather chose to exploit and gain profit from it even at the expense of those who seriously worked for- besides that, there are good compatriots who wanted to share their expertise just like those foreigners the system looked upon to.

And from these experiences no wonder why there are those who insist a fair share especially those who seriously worked for. The centuries-old unfairness has created a generation wherein people find it natural to depend on the moneylender to fund to the extent of having properties be mortgaged, if not undergoing to an agreement that appears as just when in fact it unveils its contrary- enough to mock the government’s so-called financial experts as narrow-minded misers who justifies borrowing for "various projects" or investments while at the same time giving crumbs to those who seriously and actually worked for its fulfillment, and issuing taxes directly to them.

On the other hand, nothing is wrong in needing foreign investments and foreign loans as a palliative relief to modernize the economy especially if these will “provide the country with the least costly access to needed technology, products and markets”; but at first, instead of prioritising on attracting foreign investments, the government, being a steward on behalf of the nation, should first ensure its control over key local industries, utilities, and services, as well as place national interest and public welfare above local and foreign big business interests.

Also for a country to truly benefit from foreign investments, these should be directed, if not planned in accordance with genuine domestic development, with close government monitoring and regulation, rather than letting those investments leave at the hands of interests, as they themselves sells the country altogether to the moneylenders as what Roxas sr. and his successors adhere for; for such agreements is actually a two-way road one should look on to. Countries like Sri Lanka, and a few from Africa end indebted to the Chinese as the latter provided loans on them in exchange for some agreements, so are other countries who end at the hands of moneylenders like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

With these lessons, perhaps, makes a concerned suggest that to have a productive nation first requires an immense national effort, a community-based perseverance that justifies a nation's survival, development, and maturity over those of total dependency on foreign loans and aid (in a way the late Thomas Sankara saying that "he who feeds you, controls you.") in exchange for selling its own patrimony.

From this lies a renaissance of National Dignity.

As in the past, the debate between economic protectionism and liberalisation remains especially amongst the learned. Both did spew words like "oligarchs" if not "sellouts", given their interests prevailing than those of the people- but they fail to distinguish which is protectionist or liberalist among the elites whose primary intent is to maintain their interests.

They look at Ayala, Sy, Ty, Tan, Pangilinan as examples of those elites. Of course they appear to be privileged, Noblesse Oblige-driven personages in the socio-economic arena, trying to make profit while throwing some crumbs in its tiresome subjects. They would done themselves in Barong Tagalog and singing the national anthem, putting some patriotic flavor in their statements and promising to support various forms of economic developments which includes currying foreign investment and keeping wages low for the workers; but, after hearing statements from the government promising to curb their power in favour of empowering the commons, have they already curbed? For sure apologists would have cited the examples of Lucio Tan and Mighty Corporation, if not threatening the Lopezes and Pangilinan, but how about the other bigger ones like those who ruled over the enclaves of Makati and Pasig?

So are the multinationals whom been described as an "alternative" to those oligarchs. With "economic liberalisation" presented as an alternative, the lessening of government restrictions, privatisation, and subservience to the international market has been the agenda that pleases those of the compradores and bureaucrats. They would even make various alibis such as maintaining or increasing their competitiveness as business environments, if not bluntly stating that only through globalised capitalism, with its so-called free markets and free trade, or even free borders and less to none government interventions, a literal interpetation of laissez faire, as the best ways to build wealth, distribute services and to grow a society's economy.

but come to think of it- if protectionism meant economic power at the hands of the oligarchs, then how come economic liberalisation also involves the same oligarchic entities who stubbornly keeping their interests? Isn't that Liberalisation meant dismantling their power? Yet how come the compradore-landlord nature of these oligarchs find economic liberalisation pleasing as it "updates" their antiquated existence? The ruling class hath remain united for an oligarchy to remain in power and maintain its survival. They see appeals as thoughts to toy with- the way they did made factories out of patriotic sentiment, while at the same time privatising state assets to curry outside investment. The ruling class doesn't really care about the commons despite throwing scraps and crumbs at them-for least it provides them with sustenance so to speak in exchange for unjust agreements and conditions.

In fact, some of them would even look at the example of Japan during the last years of the Tokugawa shogunate and the rise of the Mikado as the absolute ruler- it did curry foreign investment, technology, knowledge, anything necessary for its modernisation; but, the government was also involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period, as well as built railroads, improved roads, and inaugurated a land reform programme to prepare the country for further development. so was the Zaibutsus who were once former Daimyos and Samurais who end invested in the use of modern technology both for the country and their interests, others, like in the case of Matsushita, did afford to babble "social justice" as one of its policies behind their industry, as if trying to put morality in managing the entire enterprise.

So was Taiwan or even South Korea that did the same patriotic-driven procedure: It carried out an import substitution policy, taking what was obtained by agriculture to give support to the industrial sector, trading agricultural product exports for foreign currency to import industrial machinery, thus developing the industrial sector. It did raised tariffs, controlled foreign exchange, and restricted imports in order to protect domestic industry. But these came the birth of conglomerates amongst the privileged.

These experiences may sound quite decades if not centuries old, but in developing countries it continues to remain relevant given their resource, labor power, and patriotic desire for full-scale development. In fact, these countries also happened to have their own elites, but in fairness to them it tried much to prioritise national interest, the problem in the Philippines was and is- how these developments which meant for the development of the country been treated half-hearted, if not wholly rhetorical- or bluntly telling that not all of them was carrying the same mindset as Salvador Araneta or Claro M. Recto.

The Oligarchs, regardless of their adaptability to modernity, would rather act Lockean as they tried to retain a good, old-fashioned system of feudalism and slavery in order “that we may avoid erecting a numerous democracy…” It is natural for them to see an unjust order, if not distorting the idea of "noblesse oblige" for their benefit especially in a time of neoliberal-globalist "modernity". On the first place, if the Philippines experience progress, then why agriculture remains less developed than those of its neighbours? Of less inclination if not total disdain towards industrialisation and promotion of science and technology? And rather a massive consumerist base depending on consumer goods? The compradore nature of these oligarchs rather clings to their space despite recognising the need for industrialising a country abundant in resources-but will they do so? They would rather act Lockean if not almost Jeffersonian as they insist the agrarian-commercial nature of the country and hath to be retained while letting some manufacturing be set upon for a trade. In fact, speaking of that former US President, Erik Maria Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn described him "as an Agrarian Romantic who dreamt of a republic governed by an elite of character and intellect".

Perhaps in a desire to have an enlightened elite, very few of these "elites" could ever grasp the enlightenment as what Salvador Araneta or Claro M. Recto has especially if the desire is for the development of the nation and the welfare of its people, or even those of Luis Jalandoni and Jose Maria Sison who transcend their class upbringings as he favours those of the commons a la Frederick Engels whose experiences as a manager made he transcend from his background and instead favours the need for revolutionary change. All imbued with a good character and intellect, these had to go down from the hill as they heed and learn from the common folks which actually constitutes a nation.

Conclusion

Sorry if to look at the past for an example, but that past remains relevant amongst those who wanted to see the country remain contented in its setting as well as those who insist to break away from it. True that the Philippines is a wealthy country. Wealthy country whose majority of its inhabitants wallow in poverty- and everyone still always say with pride that the land is rich in natural resources from the mountain to the sea, but who is to benefit that wealth what more of the development being shown and felt upon? The late Roxas, and so is his successors, would rather say that let the foreigners do the job while his compatriots to the manual task-or as what he said:

"Some Americans are coming―trained engineers, trained technicians and technologists, trained miners, trained lumbermen, who will help us finance and develop our natural resources."

True but the question is, who is to benefit that? The people who invest their brawn or those who profit from it? In fairness, there are good foreigners who seriously and selflessly focus on developing the country, but most rather chose to exploit and gain profit from it even at the expense of those who seriously worked for- besides that, there are good compatriots who wanted to share their expertise just like those foreigners the system looked upon to.

And from these experiences no wonder why there are those who insist a fair share especially those who seriously worked for. The centuries-old unfairness has created a generation wherein people find it natural to depend on the moneylender to fund to the extent of having properties be mortgaged, if not undergoing to an agreement that appears as just when in fact it unveils its contrary- enough to mock the government’s so-called financial experts as narrow-minded misers who justifies borrowing for "various projects" or investments while at the same time giving crumbs to those who seriously and actually worked for its fulfillment, and issuing taxes directly to them.

On the other hand, nothing is wrong in needing foreign investments and foreign loans as a palliative relief to modernize the economy especially if these will “provide the country with the least costly access to needed technology, products and markets”; but at first, instead of prioritising on attracting foreign investments, the government, being a steward on behalf of the nation, should first ensure its control over key local industries, utilities, and services, as well as place national interest and public welfare above local and foreign big business interests.

Also for a country to truly benefit from foreign investments, these should be directed, if not planned in accordance with genuine domestic development, with close government monitoring and regulation, rather than letting those investments leave at the hands of interests, as they themselves sells the country altogether to the moneylenders as what Roxas sr. and his successors adhere for; for such agreements is actually a two-way road one should look on to. Countries like Sri Lanka, and a few from Africa end indebted to the Chinese as the latter provided loans on them in exchange for some agreements, so are other countries who end at the hands of moneylenders like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

With these lessons, perhaps, makes a concerned suggest that to have a productive nation first requires an immense national effort, a community-based perseverance that justifies a nation's survival, development, and maturity over those of total dependency on foreign loans and aid (in a way the late Thomas Sankara saying that "he who feeds you, controls you.") in exchange for selling its own patrimony.

From this lies a renaissance of National Dignity.